Don’t talk about features? I think you mean don’t LEAD with features

Tim Hinds

Fans of product marketing and double negatives, this is for you! Welcome to Part 1 of our 3-part blog post series: Don’t NOT talk about features! To be clear, I’m advocating for talking about features in spite of all the common anti-feature rhetoric being thrown around:

“Don’t talk about features…”

- Talk about benefits

- Talk about what problems your product solves

- Talk about business outcomes you customers have achieved

- Tell a story

Now, I don’t disagree with the second half of these statements. I think you should do all of these things at the right time and right place. It’s the “Don’t talk about features,” part that’s always seemed a little crazy to me.

Psst! You can watch the presentation here👇 if you don’t want to do all that reading.

Why you SHOULD talk about features

Functional messaging about what your features do plays a very important role in helping potential users concretely understand what in your product will give them those benefits, solve those problems, deliver those business outcomes, and provide the details in your story to make it believable.

In fact, each of these levels of messaging answers a different set of questions.

Problems:

- Do I have these problems?

- Is this product intended for me?

- Is this something I would have any interest in?

Business Outcomes:

- What’s the business impact of these problems?

- What opportunities are we missing out on by not solving them?

- What value are we supposed to get out of this?

Benefits:

- What am I going to get from using your products that will help me solve these problems?

- What will I be able to do because of the product that I can’t do today?

Features:

- What specifically in the products will give me those benefits?

- How does it work?

This last level is the product-proof level of your messaging. It should tell people HOW you’re going to do all the other stuff you claim. All these levels work together to tell your full story, but it’s the features that provide the details that make the story believable.

Why you probably shouldn’t LEAD with features

Oftentimes when people say, “Don’t talk about features,” what they actually mean is, “Don’t LEAD with features.” This means not plastering your feature list front-and-center on the website and/or not highlighting features in the subject line of prospecting emails. But even then, there are countless stories of PMMs joining companies that have grown to $5, 10, 20 million in annual recurring revenue who ONLY talk about their products and features.

I found myself and other PMMs who have been in that situation asking, “HOW?! How did they get that many people to buy the product with a bunch of ME, ME, ME, messaging? (e.g. our product is so great; our features are awesome; look at all the stuff they can do.) Where was the messaging surrounding the problems they solved and the business value they’re going to provide? Unsettlingly, most of these companies weren’t even focused on the benefits of their features.

Why the hell is this happening?

I only figured it out after two things occurred:

- Over the years, I talked to a bunch of those early customers…like a ton of them. I determined what it was about the products, the messaging, and what they were hearing from company sales reps that made them want to purchase the product in the first place.

- I re-read Crossing the Chasm, after originally reading through it during business school before becoming a product marketer. Back then, it didn’t light up the same bulbs for me like it did after I had the experience of being a product marketer, especially in these early stage companies.

Geoffrey Moore’s Technology Adoption Curve

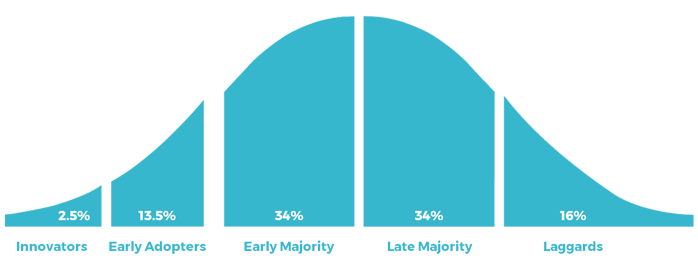

In Crossing the Chasm, there’s a technology adoption curve used by Geoffrey Moore to illustrate how different groups adopt technology. I’ve included the illustration below.

The first 2.5 percent are your innovators, followed by the next 13.5 percent which are the early adopters. Then you have the Chasm, and on the other side are the Early Majority, Late Majority, and Laggards. This last group basically only adopts new technology when absolutely forced.

Technology Adoption Mentality Breakdown

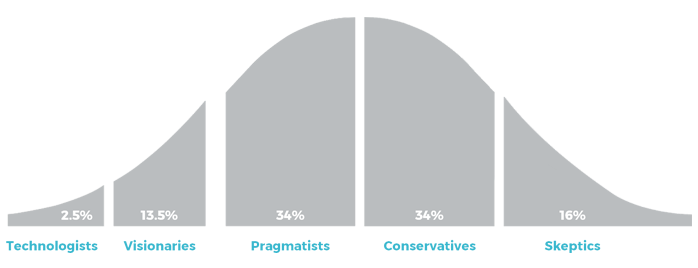

I find that it’s more useful to think about these groups based on their adoption mentalities. You can see the adoption mentality breakdown below.

For example, technologists are the first ones here and are always looking for new technologies. These are the people who check Product Hunt and Hacker News every day. They’re the ones who upgrade to an 8K TV because their 4K TV is too old. They’ll look at almost any product and its features, and if it even remotely looks like it can be used to their advantage, they’ll try it out.

The next group here, the early adopters, has the mindset of visionaries. Visionaries aren’t as much into the technology, but are more looking to solve a problem or certain set of problems. They might not be actively seeking new technology, but if you tell them how something works they have the vision to see if it solves any of their problems.

Then you have the pragmatists. Unlike the visionaries, these people need to know what problems you solve, how you’ll solve them, and for whom you’ve already solved them. Pragmatists tend to be more skeptical about what you’re offering and need to see the benefits are upfront. Typically, they don’t have the time or energy to sit there and try to look through your feature and/or product messaging to determine what’s relevant for them.

The burden of proof required for conservatives and skeptics is even heavier. After the pragmatists, you’ll need a great deal of social proof. Conservatives specifically need to know that there are a lot of other people already using the technology and that it’s something they need to be doing because they’re behind the curve.

How to apply this to features and talking about features

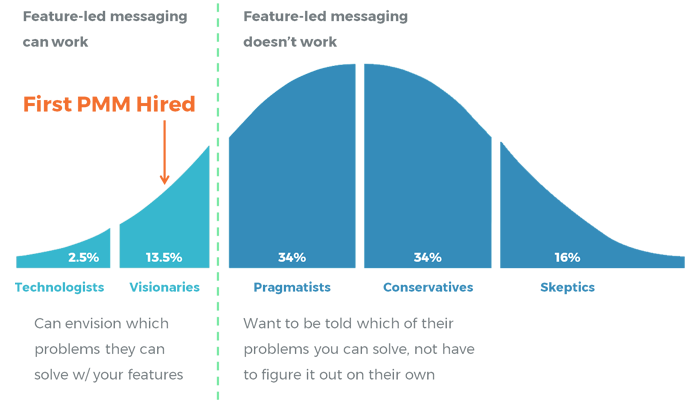

Most often, technologists and visionaries are able to envision which problems they can solve with your features. You don’t have to spell it out for them. These groups can actually be really helpful for you early on whenever you’re trying to jump the Chasm between the visionaries and pragmatists. They’ll help you understand which problems you solved that are the most valuable to them, which problems you’ve solved best with your products, and which features helped them to solve those problems.

By creating messaging around this information initially, you’ll have relevant messaging for the pragmatists when they come. As I mentioned, they don’t want to have to figure things out on their own. Right away, they’ll need to know which of their problems you can solve.

Before you hit the Chasm, feature-led messaging can work. However, you would also need a good product that people love, truly differentiated features, and be lucky enough to find the early adopters. Kind of a big caveat.

Early adopters make up 16 percent of the market; if you lead with features (i.e. covering your website with feature messaging in an attempt to hit every potential person who might be in that market), only 16 percent of people are going to get it!

For the other groups‒the other 84 percent of people‒feature-led messaging won’t get the job done. They require other pieces of information including: the problems you’ll solve, what benefits you’ll provide that helps them solve these problems, what the business impact will be, and who else has already solved those problems.

Enter the PMM

It ends up being somewhere around the late visionaries and the early pragmatists when a company typically brings in its first product marketing manager. That’s when we start asking, “How did we grow to this size just talking about features this whole time?” We review the company’s messaging and all the content they’ve produced‒it’s filled with all this feature-focused, ME ME ME messaging.

Time for the rewrite. We start with problems or business outcomes, then we start changing the feature messages so that they’re written more like benefits. This lets people know what it is that the feature is going to do for them versus what the feature does itself.

However, there’s been some evidence lately that suggests that we may be overcorrecting here. In Part 2 of our Don’t NOT talk about features series, I’ll dive into this overcorrecting behavior and explain how you can avoid turning your business outcomes and benefit messaging into unbelievable fluff.